After a remarkably encouraging, supportive and stress-free viva, which gave me a big confidence boost, I jumped straight into full-time temping admin work in February, leaping at the chance to gain some stability and normality. I've since found a slightly more secure full-time job, but it feels very much like a compromise whilst I try and figure out what to do next and how to get back to research and writing – and disseminating my PhD. I've been writing more this year, primarily art criticism, and finally regaining some enjoyment from it. These are some of my highlights of 2018, cultural and otherwise:

Art

The first exhibition of the year I saw was the best I’ve seen yet at the Tetley in Leeds. Saelia Aparicio made the best use of the former brewery’s dark, wood-panelled rooms I’ve seen so far, including neon sculptures commenting on issues such as the housing crisis. The Tetley closed the year with the equally good Bus2move by Simeon Barclay, which explored the inspiring cultural and social history of the city's Phoenix Dance Company through archival film, as well as the significance of movement, music and dance in Barclay's own life.

I’d never heard of Polish artist Alina Szapocznikow before, but an illuminating retrospective at the Hepworth in Wakefield showed her development from a Soviet Realist sculptor to using polystyrene casts of her own body, decaying materials, photography and film to explore not just the body and the self but experiences such as cancer, femininity and the way in which women are seen. Often borrowing from the surreal and grotesque – for example disembodied female body parts repurposed as lamps, cushions cast from her stomach and bulges reminiscent of amniotic sacs or tumours – I felt that her work contained a lot of humour.

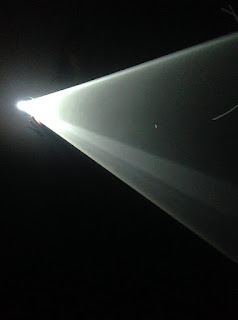

Later in the year, I also enjoyed Anthony McCall’s Solid Light Works at the Hepworth, where a bustling public explored his countercultural light beams and smoke in darkened rooms, displayed alongside his equally fascinating methodological workings out and diagrams.

Another early 2018 highlight was the collective Brass Art’s retrospective that-which-is-not at Bury Art Museum. Drawing on archives, and using techniques such as neon, glass, light and 3D printing, the work explored visibility and invisibility and the ways in which women can insert themselves into artworks and collections.

My favourite exhibition of the year was Andy Holden’s Natural Selection at the Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne, a collaboration with his father, Peter, an ornithologist, which explored the natural and human activities of nest building and egg stealing, and the changing politics and ethics of acquiring, collecting and displaying archival and museum objects from the natural world, through sculpture, installation and film.

Runner up was Zoë Paul’s La Perma-Perla Kraal Emporium at Spike Island in Bristol, drawing on traditions of meeting spaces and public discussion fora from Paul’s native Greek culture. The exhibition brought visitors together for discussion around a four-headed fountain, and Penny Royal tea served from a grotesque ceramic head, inviting the public to make clay beads for use in future editions of her large-scale ceramic curtains.

Despite two visits, I didn’t feel I got a full grasp of Liverpool Biennial, in part due to the predominance of lengthy and often highly politicised video work. Of what I did see, I enjoyed Annie Pootoogook’s drawings of everyday Inuit life at Tate Liverpool and Ryan Gander’s large-scale play-inspired sculptures, drawing on elements of the architecture of Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral, and works on paper, developed collaboratively with local school children at the Bluecoat. Other strong work at the Bluecoat included Suki Seokyeong Kang’s interactive work combining sculpture and movement, and Abbas Akhavan’s commentary on the cultural destruction of Isis. Such large-scale programmes always provide opportunities to visit unusual buildings and venues, and out of these one of the highlights was Taus Makhacheva’s installation at the former girls’ school Blackburne House, where we watched visitors receiving a facial treatment whilst listening to a thoughtful narrative bringing our attention to the materiality and temporality of sculpture. The Biennial also drew me into Liverpool University’s fantastic Victoria Gallery for the first time, where Holly Hendry’s sculptures appeared among the eclectic collections like strata of rock embedded with strange objects. One of the best works I saw at the Biennial was here, too, Taus Makhcheva’s film ‘Tightrope’, which set ideas about art, culture collecting against the mountainous landscape of Dagestan. The other two standouts of the Biennial were Madiha Aijaz’s film ‘These Silences Are All the Words’ at Open Eye, which explored cultural and linguistic guardianship in Pakistan, and Mohamed Bourouissa’s films at FACT, including his short documentary ‘Horse Day’ about the staging of an equestrian themed neighbourhood event in Philadelphia. I’m looking forward to seeing some of these works again, and catching some of those I missed, as part of the Biennial’s northern touring programme in 2019.

I was surprised by how much I enjoyed William Kentridge’s Thick Time at the Whitworth Art Gallery. His mesmerising, dreamy installations and films, drawing on dance, music and movement, made the everyday magical and surreal, from the stovetop coffee pot shooting for the moon, to the ants tracing paths across the floor, to the man wandering through an animated dictionary, to a giant breathing machine imitating the stuff of life and time.

Towards in the end of the year, Hannah Leighton-Boyce’s solo exhibition Dreaming of Dead Fish was a brief intervention into Warrington Museum & Art Gallery. It provided a welcome opportunity to visit this extraordinary example of a municipal museum, with its in-tact 1930s collections and displays which categorise and explore the natural world in incredible detail, from trees to the titular dead fish. Leighton-Boyce presented us with archaic everyday objects, showing us how our understandings of objects are changed by the decisions made about what is collected and how it is classified and displayed. Here, these objects included uranium green vanity trays, removed from their usual function and displayed upside down and face-to-face. Projected on the museum’s walls, one pair of vanity cases revealed barely perceptible patterns and reflections in the shiny parquet floor. Others, covered in a layer of velvety soot and turned awkwardly away from the viewer towards the wall, asked us to look at them closely in order to figure out what they were. Antique terrarium covers labeled ‘trout’, meanwhile, sat face down, and a slide projector showed a burned surface which revealed its own pattern in its destruction, its original content disfigured yet still faintly discernible.

A late highlight of 2018 was Emma Talbot’s densely worked silk wall hangings and shiny textile sculptures resembling bodily forms at Caustic Coastal in Salford. Incorporating texts, they gave voice to inner thoughts and asked questions about our place in the world and how we come into it, navigating between myth and reality and highlighting issues around regeneration and city life in a gallery space overlooking the multiple cranes of a rapidly developing skyline.

Other highlights throughout the year included the Sonia Boyce retrospective at Manchester Art Gallery, exploring identity, culture, race, tradition and history, Phil Collins’ irreverent, pop cultural works at Home, where a concern for social issues lay under a sheen of superficiality, and Lubaina Himid’s narrative characters installed at the Harris in Preston.

The Turnpike Gallery in Leigh continued its strong programme: particular highlights were two exhibitions drawing on the material and cultural legacy of the area’s coal mining heritage, by Mary Griffiths (read my review for Corridor8 here) and Nick Crowe and Ian Rawlinson (read my review in Art Monthly issue 414).

I was finally tempted to the Grundy in Blackpool for 'Northern Lights', Chris Paul Daniels' irreverent, behind-the-scenes look at the Blackpool Illuminations (read my review for Corridor8 here).

At arts centre Friche De Belle Mai in Marseille I enjoyed Jean-Luc Brisson’s watercolours and cross-hatched drawings combining natural, observed and imagined forms in fantastical combinations of clouds, frogs, angels’ wings and birds.

I braved the crowds at Tate Modern for the Anni Albers retrospective, to learn more about her time as a student at the Bauhaus and teaching at Black Mountain Collage, and see her functional, architecturally inspired and pictorial weavings, which incorporated and experimented with different textures, techniques and types of thread. I was fascinated to learn about how she drew on ancient weaving techniques and was inspired by the patterns of early Latin American civilisations, and also enjoyed her jewellery reinventing everyday objects such as hair pins, corks and eye screws.

Finally, the Encore Room, a wood burning sauna and discussion space hosted by artist Olivia Glasser, was a welcome temporary installation in the courtyard at Islington Mill in Salford.

Film

‘Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri’, managed to be both moving and funny, despite the gravity of its subject matter.

‘The Square’ was excruciatingly funny and cut close to the bone in its depiction of the pretensions of the artworld.

I found ‘A Fantastic Woman’, with its phenomenal performance by Daniela Vega, heartbreaking.

Afghanistan-set animated film ‘The Breadwinner’ demonstrated the power of storytelling, depicting a young girl’s courage in the face of repression and brutality.

‘Dark River’ explored family relationships across a long, dour Yorkshire summer that ended well for no-one. The latest in a run of films showing how grim and hard life can be in the countryside, it started and ended with ‘An Acre of Land’, an impossibly beautiful version of a traditional tune sung sparsely and plainly by PJ Harvey.

Yiddish-language film ‘Menashe’ gave a Jewish view of Brooklyn, depicting a tender father-son relationship striving for normality despite restrictive cultural conventions.

Taking place over a heady summer in claustrophobic New York City, ‘Skate Kitchen’ navigated female friendship, relationships and the city through the filter of youth culture and Instagram; the film was also perfectly matched to its soundtrack. Excitingly filmed, ‘Skate Kitchen’ showcased the skill, attitude and dedication of the real group of skaters on whom it was based. Though beset by gender wars, ultimately the film showed that the sexes aren’t so different after all, and that ‘girls’ can do anything ‘boys' can, particularly when it comes to skating.

Nineties-set film ‘The Miseducation of Cameron Post’ was a subtly shocking and moving drama about gay conversion therapy and friendship in beautiful setting. Exploring identity and rebellion, central character Cameron was notable for her vulnerable strength.

Japanese film ‘Shoplifters’ was a beautiful portrayal of child friendship and relationships across generations with a surprising twist, exposing how normality, family and belonging is constructed. There were excellent performances from all, but particularly the children and the grandmother.

‘Peterloo’ was ponderous but contrary to popular opinion I didn’t find it overlong. It succeeded in showing the build-up to the massacre of 1819 and giving a sense of how the protest came about in impressive detail, from extensive talk and debate to practise marching on the moors above Manchester, among the beauty of the English landscape, to introducing the arrogant yet naïve orator Henry Hunt with his insistence on non-violence. Set in a Manchester that’s now unrecognisable, and making simple but effective use of music and song, the film captured the poverty and hunger of the age and the class-riven inequalities that existed. Sometimes these class representatives came across as caricatured – the cackling rich and wide-eyed poor – yet this worked to comic effect in the grotesquely made up and debauched yet callous figure of the Prince Regent, adding some much-needed moments of levity to the film.

Two black and white films were both heavily hyped this year, 'Cold War' and 'Roma'. I vastly preferred the gorgeously filmed 'Roma', an enthralling and affecting portrait of the relationship between an upper-middle-class white family and their Mixteco maid, set against the political protests of 1970s Mexico City and replete with atmospheric details, to the overly stylised 'Cold War'.

I saw a couple of good urbanism documentaries. ‘New Town Utopia’ was set in the Essex New Town of Basildon, evaluating whether contemporary life in the town matches up to its’ planners aspirations, and introducing us to a range of people who had made a home there.

Another large-scale experiment in planning was the subject of the documentary ‘Brasilia: Life After Design’. Far from portraying the Brazilian capital as a utopia, the filmed presented Brasilia as a sprawling, traffic-ridden dystopia, and highlighted the ways in which the city’s growth was anticipated through planned satellite cities which limited the number of people the city could accommodate. It suggested that the precarious existence of millions was characterised by faith, class divides and a daily grind of unreliable public transport, long journeys to work, protest and hundreds of people queueing for government exams in an attempt to create a better life for themselves. In spite of this, the film showed the diversity of the city and a spirit of resourcefulness and making do. Although the city’s famous architecture seemed strangely in the background, it was explained with enthusiasm by Willian, the softly-spoken and thoughtful souvenir seller by day, phoneline counsellor by night, who proved the star of the film.

‘Edgar Wood: A Painted Veil’ was a charmingly enthusiastic and eccentric documentary about the architect, originally from the former mill town of Middleton near Rochdale. The whistlestop tour of his domestic, church and school buildings in Middleton, Huddersfield, Cheshire and Stafford positioned him as an overlooked genius and at times overstepped the line towards hyperbolism. Placing him in the avant-garde of art nouveau and modernism, it explored his international influences, which led to him eventually settling in Italy.

Soundtracked by the distinctive guitar playing of Vinni Reilly, another documentary, ‘The Last Clarion House’, visited the last surviving clubhouse serving the socialist Clarion cycling movement, near Pendle in Pennine Lancashire. Situating its history in industrial Lancashire, the film considered landscape, land ownership and social change, from the building’s beginnings as a communal leisure facility for town-dwellers to escape from the smoke, to a volunteer-run tea stop serving those who continue to stop there, including an 87-year-old cyclist.

‘Matangi/Maya/MIA’ presented the pop star MIA as an articulate, confident young woman and artist in all senses, showing her work as a filmmaker alongside her career as a musician. Throughout the course of the film we saw her grow up and learn, and grapple with the best way to make a difference.

Documentary ‘Nae Pasaran!’ movingly brought together two sets of men – a group of former Chilean political prisoners and a group of principled engineers and trade unionists – separated across continents yet linked through a strike in a factory in 1980s East Kilbride which blocked the repair of fighter bomber engines destined for Pinochet’s Chile. Giving voice to these now elderly men’s experiences alongside solidarity campaigners and human rights organisations, the film highlighted the complicity of foreign governments and the number of unanswered questions that remain.

‘Strata’, a film by the artists Nick Jordan and Jacob Cartwright, placed Barnsley’s coal mining heritage in a historical and international context, telling stories of former miners – alongside their wives – and highlighting masculinity and labour, education and empowerment alongside the natural environment and biodiversity of former mining sites. Ultimately, the film drew our attention to the working conditions of today: zero hour contracts in call centres, and low-paid work in the care and service economy are often all that’s on offer in areas where the local industry has closed down.

Scottish artist Rachel Maclean’s film ‘Make Me Up’ was part of the nationwide 14-18 Now programme, commemorating the centenary of the First World War. Using her trademark pastel-lurid colours, Maclean transformed the derelict, modernist St Peter’s Seminary at Cardross into the fantastical setting for a grotesque nightmare; Maclean’s attention to detail extended as far as the use of breasts for doorknobs. Assuming the character of a stern, matronly figurehead, delivering lectures on civilisation taken directly from the work of late broadcaster and writer Kenneth Clark, Maclean presided over dressed up, dollish caricatures of women, each with their own Tatty Devine-style nametag yet stripped of their capacity for individual action and rendered mute. Intended as a comment on art criticism and the male historical canon, ‘Make Me Up’ made links between artistic representations of women and women’s voices and representation culturally and historically, most visibly in the sudden appearance of a Suffragette slashing a painting in an art gallery. Whilst exploring big issues such as feminism, femininity, solidarity and sisterhood, the film also remained very funny – something that was more important than ever as the sickening plot twist dropped like a bad punchline. Maclean’s real talent is for making work that chimes with the concerns of the now – ‘Make Me Up’ resonated not just in a culture of social media likes, vlogging and selfies, but with the post-#MeToo context.

Trips

In January I went to see Bingley’s five rise locks, an amazing feat of industrial engineering, which inspired William Mitchell’s fibreglass mural for the Bradford and Bingley Building Society’s now demolished HQ in the town.

I also made my first ever visit to the north Kent seaside town of Herne Bay, with its lively pier where the traditional fare of doughnuts and chip butties mixed with the newer phenomenon of ‘street food’, and helter skelters and gallopers sat next to a range of inventive knitted decorations, from tablecloths and seasonal greetings to representations of sealife and commemorations of the RAF. I walked to Reculver towers under its muddy cliffs, with piles of shells crunching underfoot.

After years of aspiring to visit Milton Keynes, I found it to be a very stressful experience: I spent hours wandering around its famous roundabouts and ‘greenways’ in circles, looking for its well-hidden and misshapen concrete cows. Milton Keynes seemed a dystopian, disorienting sprawl, overhung by the constant sound of traffic, its grid system swallowing up thatched villages. Its centre consisted largely of cars and carparks, punctuated with anodyne public art.

My first ever visit to Croydon, where I headed straight afterwards, was a relief after the lifelessness of Milton Keyes, although the town’s general dereliction contrasted sharply with the scale of new development going on.

From here, I went to see the infamous Crystal Palace dinosaurs, huge concrete representations of what the Victorians considered dinosaurs to look like, which lounge in the sun on an island in the centre of Crystal Place Park.

My quirkiest trip was a public-transport themed excursion, organised by my friend Marcelle Holt, which started by taking the Hulme’s Ferry – operated by one man and summoned by a makeshift gong – across the River Irwell, between the outer Trafford and Salford suburbs of Davyhulme and Irlam, and concluded with a visit to meet some weekend flyers at Salford’s Barton Airport.

In Haslingden, Pennine Lancashire, I went to see the Dave Pearson studio, where 15,500 paintings, collages, etchings and drawings by the late artist and teacher cram a terraced house. My favourites were dark, shadowy works drawing on traditions such as the Abbots Bromley Horn Dance, calendar customs, and strange and collective elements of everyday English life.

I lost my heart to Marseille, a charismatically chaotic Mediterranean city nestled between the scenery of the mountains on all sides and a rocky coastline pocked with small islands. A hotel room in Le Corbusier’s Unité d'Habitation gave spectacular views over the city and a series of atmospheric roof-top sunsets. The city’s neighbourhoods were diverse, with the older areas of the city resembling the quirky bits of Granada and Barcelona’s El Raval neighbourhood: in Le Panier, close to the old port, small streets were planted with residents' small-scale yet determined attempts at maintaining greenery. In general, the city was surprisingly green, with cacti and extravagant flowers growing wild everywhere, and parakeets and lizards adding to the street life. A bus to the outskirts of the city, and a walk through pine-scented air, led to the Calanques – a series of secluded coves where the sea was green and clear.

The long train journey through the French countryside, through fields and fields of sunflowers, their withering, browning and droopy heads turned towards the sun, and along the coast through dense pine forests, and orange rock, was an experience in itself. Although I had been warned, I wasn't prepared for just how touristy and built up the Côte d'Azur was. I stopped off in the quaint town of Fréjus to visit the Jean Cocteau-designed Chapelle Notre-Dame-de-Jérusalem, a small gem of chapel in a pine forest above the town, bejewelled with bright Cocteau-designed murals and stained glass, where I was the only visitor.A touristy, crowded resort town, Nice couldn’t help but be an anticlimax after Marseille. I stayed in Les Musiciens, where all the street names referenced classical composers. Here, the sea was noticeably darker – a royal blue –and the English, influence was apparent in the names of the streets and large hotels. Underfoot, the striped stones from the dry riverbed that runs into the see rubbed my already blistered feet. The sense that this was a playground for the wealthy was reinforced by the big boats in the harbour. A highlight was stumbling across the work of Denis Morog, a French equivalent to William Mitchell, in the form of huge textured panels flanking a corner building.

Nearby Villefranche-due-Mer, a town with a fortress, harbour and covered fourteenth century street, was more relaxed. Cocteau’s beautiful murals in the tiny Chapelle Saint-Pierre drew on aspects of everyday life in the town, from women working in the fishing industry to gypsies and the jazzy guitar playing of Django Reinhardt.

Menton was thankfully less touristy and crowded than much of the nearby coastline. I wandered the narrow, steep-stepped streets of the Italian-influenced old town semi-lost, and picked oranges. Locals get married underneath frescos by Jean Cocteau in the town hall. His work in the marriage hall depicts young lovers in local dress and hats, and blends human, fish and animal features, creating patterns out of everyday life. Cocteau’s contribution is not limited to the walls and ceiling, but includes a pair of mirrors and panther carpets.

Menton contains not one but two Cocteau museums. At the main Cocteau museum, which showed off the range of diversity and media in which he found expression, from painting and printing to film and poetry, I particularly enjoyed his work in glass, such as a Madonna and Child and depiction of the moon. Alongside his ceramics, the Bastion, a former fort, showed how Cocteau adapted the traditional local mosaic technique using found stones to depict imagery such as lizards.

Back in the UK, I headed to Weston-Super-Mare to wind down from a job interview in Bristol. Although it had the familiar run-down feel of a seaside town, its expansive sandy beach offered views of the nearby hills and islands.

Rivington Terraced Gardens, built by Lord Lever into the hillside above Bolton, was magical as summer turned to autumn. Steams and waterfalls wound their way through the woods, and russet leaves gathered in pools on the steps and stone paths that make their way up and down the hillside, past strange, crumbling follies. Rivington Pike gives panoramic views over a reservoir, the moors, the town and the terraces of Bolton Wanderers Football Club.

I went to the beautiful Georgian town of Chichester in West Sussex for the first time to visit the fantastic Pallant House Art Gallery. Pallant House, housed partially in an old home and partially in a modern extension, showcases a collection of twentieth century artworks alongside interventions into the building and its collection by contemporary artists (and a comprehensive bookshop!). I also enjoyed wandering the city's walls and visiting Chichester Cathedral, where modern additions commissioned by Canon Walter Hussey include paintings by Hans Feibusch and Graham Sutherland, a stained glass window by Mark Chagall, and a vibrant, semi-abstract tapestry by John Piper.

Swims

On a snowy day with a freezing wind, I warmed up with a very warm sauna at Bingley’s 1927 pool, and swam under a painted vaulted ceiling and stylised windows. It’s the only pool I’ve ever visited which retains slipper baths, and was also notable for its extremely friendly people.

Despite its reinvention with a fancy café – where a waterside wedding reception was taking place – Brockwell Lido retained a real community feel, and a multicultural, multilingual atmosphere. Another bonus point was that the water was not too cold!

It took me until 2018 to find out that it’s possible to swim a 450-metre course at Sale Water Park, a small lake just off the M60 motorway yet surrounded by greenery. With the water a balmy 22 degrees, it was full of Mancunians enjoying the sunshine.

I returned to Lyon especially to swim in Piscine Tony Bertrand, an outdoor pool on the banks of the Rhône with four huge flag towers and chunky concrete reliefs. Built in 1966, the architecture was a major attraction but it also caters for all tastes with jacuzzis and a water slide.

The highlight of the year was undoubtedly swimming in clear Mediterranean waters from the rocks at Malmousque and Endoume, Marseille, overlooking small islands.

One of the coldest swims was in the weed-filled estuary water of Whitstable, surrounded by the oyster fishing trade.

The water was also extremely, uncomfortably cold at the freshwater lido Pells Pool in Lewes.

Bike rides

This summer, I finally explored Salford’s version of the Fallowfield Loop, the very green and pleasant Roe Green Loop Line, which runs between the villagey suburb of Monton and Little Hulton, on the outskirts of the city. From an elevated perspective, the loopline looks down onto woods, fields and cows; it feels and smells like the countryside. Unlike the Fallowfield Loop, the former station platforms are still in place.

I followed another old railway line, the Middlewood Way, to Bollington, a picturesque Cheshire village of former mills, terraces and back-to-backs in a uniform warm grey stone. Local viewing point White Nancy, on the Gritstone Trail, offers views all around, of the telescope at Jodrell Bank, the skyscrapers of Manchester and high-rises of its outlying towns, and the rolling countryside divided into green plots with drystone walls.

I also went out eastwards along the Peak Forest Canal to the green, former industrial edgelands of the Tame Valley, where farms and stables made out of old railway carriage stables meet suburban cul-de-sacs.

On a windy August day in Kent, I followed the Saxon Way out from Faversham’s boatyard into a flat, bleak, marshy landscape, past cows grazing between the sea wall and golden fields of wheat, to the shoreline, where the Swale meets the sea with a crust of oyster shells, driftwood and dried seaweed. On the estuary, a barge passed with its sails up.

Radio

I learnt a lot from ‘The Lost Art of Churches’, a documentary on Radio 4 Extra exploring twentieth century and modern-day art in churches, and issues around its value, conservation and upkeep.

Television

Aside from the odd episode of University Challenge, the only 2018 TV I managed to watch was Black Mirror special 'Bandersnatch'. In an age where traditional television seems less and less relevant, and has to compete with a myriad other forms of entertainment for our attention, Charlie Brooker changed the game with an interactive and surprising experience, that took us back to the 1980s world of early videogames in order to explore questions about action, agency, our capacity to make decisions, and the part they play in how we think about ourselves, our relationships and our past, present and future lives.

Records

Tune-Yards went all eighties dance on ‘Look At Your Hands’.

I couldn't help but like the taut, New Wave-style punk of Shopping’s ‘Asking for a Friend’ because it features Rachel Ags from two of my favourite bands, Trash Kit and Sacred Paws.

Both with Fiery Furnaces and as a solo artist Eleanor Friedberger has spent years producing top-rate pop music so catchy it always sounds like you’ve heard it before: this year I particularly enjoyed ‘In Between Stars’.

Rolling Blackouts Coastal Fever’s ‘Time In Common’ appealed to me by sounding like an Aussie take on the Feelies.

The Orielles’ Silver Dollar Moment is a great debut record, bringing together indie pop with great pop-dance tunes.

Lastly, I was an extra for Manchester pop legend Edward Barton’s low-budget pop video set at a high school reunion. After miming the words multiple times, I had the tune to the catchy song, ‘Best Laugh’, in my head for months.

Gigs

Tune-Yards showed a pop star presence at Manchester’s Albert Hall. The drums and bass of a stripped-down three piece were the backdrop for Merril Garbus’ extraordinary voice, sometimes sweet and at others unabashedly raw and powerful. Many of the songs featured the ukulele we’ve grown used to, but with the addition of a lengthy dance sequence in the middle.

Ghanaian disco star Ata Kak had joyous energy at Band on the Wall, accompanied by a much younger band and prompted frenetic dancing in an even younger audience.

I don’t know what I expected when Terry Riley and his son Gyan Riley performed together in a concert at the RNCM, but there were a lot of surprises, including how conventional it was. This was a gig that was warm, human, jazzy, joyful and even funky. Terry Riley switched between piano, melodica and synthesiser, and between musical styles ranging from improv and chanting to what sounded like an evangelical hymn. Gyan Riley’s fast, urgent guitar playing drew on flamenco and classical styles, demonstrating a virtuosity that never became noodly or gratuitous. Between them, they showed a real camaraderie and enjoyment of playing together.

Books

John Boughton’s ‘Municipal Dreams: The Rise and Fall of Council Housing’ was a welcome development from his blog, giving an overview and history of social housing in England and creating a national picture out of small detail (read my review for Manchester Review of Books here).

Sally Barrett’s ‘A Life’s Work’ is a collection of small stories in poem form.

‘Radical Essex’, published by Focal Point Gallery, offered a welcome collection of different perspectives and alternative, often radical, histories of the often-maligned county, exploring its innovations in architecture and popular culture (read my review for Manchester Review of Books here).

‘Prefabs: A Social and Architectural History’ by Elisabeth Blanchet and Sonia Zhuravlyova gave an illustrated history of prefab housing, which was both thorough in its detail and an accessible and enjoyable read (read my review for Manchester Review of Books here).

‘All In the Downs’ by Shirley Collins offered an insight not just into her work and career, but into life in post-war London and Sussex (read my review for Manchester Review of Books here).

Theatre

I enjoyed two mid-20th century American family psychodramas this year, Eugene O’Neill’s ‘Long Day’s Journey Into Night’ at Home and Arthur Miller’s ‘Death of a Salesman’ at the Royal Exchange.